Key Takeaways

- Zinc meaningfully outperformed the broader commodity basket during the month of April.

- Investor sentiment has started to improve and there is considerable room for it to go further.

- Zinc stands to benefit from the deployment of renewable energy worldwide given its use in galvanising steel for wind turbines.

- Related ProductsWisdomTree Energy Transition Metals, WisdomTree Battery Metals, WisdomTree Zinc, WisdomTree Zinc – EUR Daily HedgedFind out more

Zinc had a very strong month in April. The metal was up 22.5% during the month becoming not just one of the hottest metals but one of the top performing commodities across all sectors1. Over the same period, the Bloomberg Commodity Index was up 3.9%2.

But when assessing performance, time horizon matters. The metal is still down considerably compared to its peak in 2022, in line with other industrial metals that have been hit hard by rising interest rates and expectations of economic weakness.

Can the metal regain its highs and potentially go further? In this blog, we explore some of the cyclical and structural forces driving zinc.

The demand and supply balance

According to the International Lead and Zinc Study Group3, global demand for refined zinc metal is projected to increase by 1.8% in 2024, reaching 13.96 million tonnes. While China, a major consumer, is expected to see a more modest growth of 1.4%, other countries like India, Italy, Japan, Turkey, and the United States are anticipated to witness rising demand. However, demand is forecasted to decline in Australia, Bulgaria, the Republic of Korea, and Spain. On the supply side, world zinc mine production is expected to rise by 0.7% to 12.42 million tonnes in 2024. This increase is mainly driven by anticipated production hikes in Australia, Mexico, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, although decreases are expected in Canada, South Africa, the United States, and Peru. European mine output is anticipated to decline due to mine suspensions, despite the commissioning of new mines.

Looking at refined zinc metal output, the global market is expected to see a modest increase of 0.6% to 14.01 million tonnes in 2024. While Chinese production is predicted to grow by 1%, European output is forecasted to decline by 1.8% due to smelter idling and suspensions. Overall, the global market balance suggests a surplus of refined zinc metal, with a surplus of 56,000 tonnes anticipated for 2024. This is much smaller compared to a surplus of 205,000 tonnes in 20234.

The role investor sentiment can play

Arguably, investor sentiment towards industrial metals has been excessively bearish throughout 2023 and the first quarter of 2024. Things have started to turn since April with copper leading the revival and others following suit. The Bloomberg Industrial Metals Subindex was up 14.4% in April compared to 3.9% for the broader Bloomberg Commodity Index5.

We think good economic data from the two biggest economies, US and China, has helped contribute to this improvement in sentiment. Although growth has not been stellar, the US has certainly not fallen into a recession. Moreover, indicators like Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) have been in expansionary territory for the first four months of the year6. Similarly in China, whose manufacturing activity has an even larger bearing on industrial metals, Manufacturing PMI has shown expansion since November last year7.

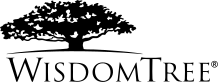

Investor sentiment, as measured by net speculative positioning (see figure below) has risen in April but remains around the 5-year average and has room to rise further. This will largely depend on whether investors perceive the persistently hawkish stance from the Federal Reserve as damaging to the steady growth numbers or not.

Net speculative positioning in zinc futures has risen recently

Source: Bloomberg, data as of 02 May 2024. St dv is standard deviation. LME is the London Metals Exchange. Net positioning is shown in terms of number of contracts. Historical performance is not an indication of future performance and any investments may go down in value.

Promising energy transition prospects

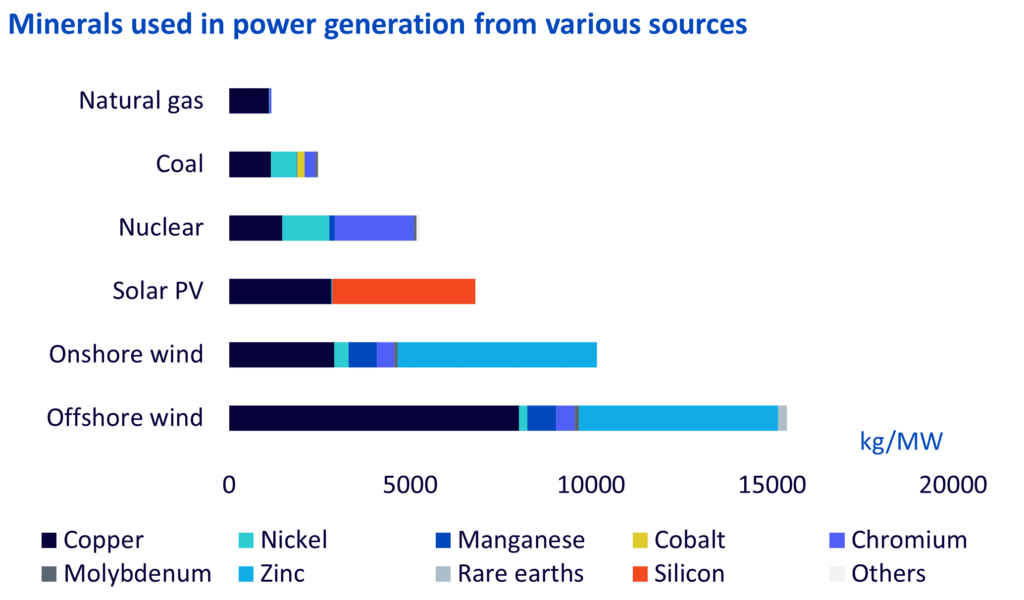

Zinc’s primary industrial use is in galvanising steel for protection from corrosion in everything from buildings and bridges to transmission towers and wind turbines8. According to the US Geological Survey, between 66-79% of the total mass for a wind turbine is made of steel. Each turbine, therefore, depends heavily on zinc for its long-term endurance. This is especially true in offshore wind where turbines are even more vulnerable to damage from the elements.

Source: IEA (2021), Minerals used in clean energy technologies compared to other power generation sources, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/minerals-used-in-clean-energy-technologies-compared-to-other-power-generation-sources, Licence: CC BY 4.0. PV refers to photovoltaic.

According to the International Energy Agency, generating one megawatt (MW) of power from wind requires 5,500 kilograms (kg) of zinc. In contrast, there is almost no zinc required for producing power from coal or natural gas. With world leaders having pledged to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030 (at the latest United Nations Climate Change Conference COP28), the long-term prospects for zinc demand growth appear strong.

Sources

1 Source: Bloomberg, based on the price change of the generic first zinc futures contract.

2 Source: Bloomberg.

3 International Lead and Zinc Study Group April 2024 press release and forecasts.

4 International Lead and Zinc Study Group February 2024 press release and forecasts.

5 Source: Bloomberg.

6 Sourced from Trading Economics citing S&P Global data.

7 Sourced from Trading Economics citing Caixin data. 8 Feeco International.

it amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.