Key Takeaways

Many companies will need carbon credits/offsets, in addition to directly reducing their emissions, to lower their carbon footprints enough to achieve net-zero emission targets.

Carbon credit markets offer “positives,” such as financial incentives to use green energy and develop new technologies, but downsides include “greenwashing” risks.

Emerging markets play a special role in global carbon markets and could benefit from an inflow of capital, but there is a risk of exploitation.

The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and the Paris Agreement of 2015 established international goals for reducing carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, leading to national emissions targets and regulations to enforce them. Companies around the world are looking to reduce their carbon footprints in two ways:

Reducing emissions and switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

Purchasing “carbon credits,” “carbon offsets” or both in the carbon credit market.

The basic idea of these markets is that by paying for the right to emit CO2, businesses help to finance reductions in greenhouse gas emissions elsewhere. Even companies not required to reduce their emissions are pledging to do so in response to substantial pressure from various stakeholders. This is increasing demand for, and raising the prices of carbon credits and offsets, creating a funding source for activities and technologies that reduce or absorb carbon emissions.

More than two-thirds of countries plan to use national or regional carbon markets to meet their commitments under the Paris Agreement (note that the U.S. does not have a national market for carbon credits, and California is the only state with a cap-and-trade program).1 Even where emission reductions are not mandated by law, companies in a number of industries will have to use carbon offsets to reach net-zero commitments. For example, in 2016, the International Civil Aviation Organization adopted the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation to address CO2 emissions in the aviation industry.

Carbon Credits and Carbon Offsets

Definitions, please: People often use the term carbon credits, also known as carbon allowances and carbon offsets, interchangeably. While they have similar goals — to increase the cost of emitting greenhouse gases to the point where alternatives are more economically appealing — credits and offsets arise from different sources.

What Are Carbon Credits?

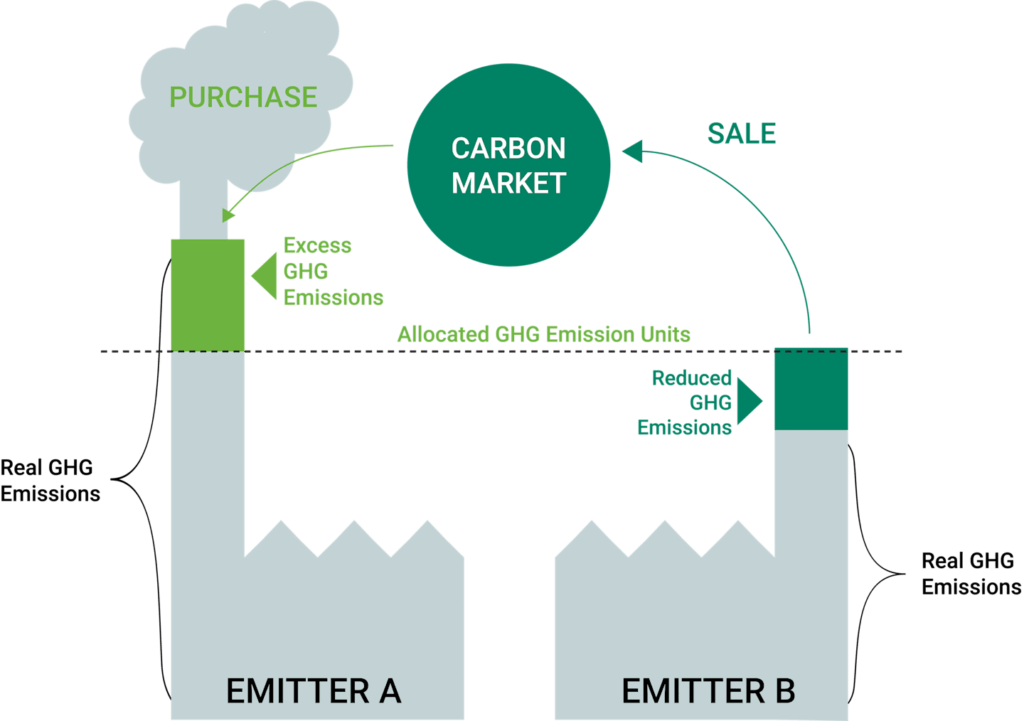

Carbon credits (or allowances) are created via a cap-and-trade system that defines the amount of CO2 emissions a given company is allowed to generate without paying a fine. Each company is given carbon credits, initially sold or allocated by the government, up to its limit. Companies that emit less than their credits allow can sell excess credits to others that do not have enough, creating a carbon credit market See Figure 1. Companies’ emission caps are set to decline over time, increasing the value of these carbon credits.

A business will weigh the cost of buying credits against the cost of buying and/or investing in clean energy and finding other less carbon-intensive means of operating. As demand for carbon credits increases — either because industries seek to increase CO2 emissions to support their activities or because emission caps tighten, or both — the price of carbon credits increases. This creates a financial incentive to use greener alternatives and invest in new technologies that reduce emissions, making them more cost competitive.

Figure 1 | How an Emission Trading System Works

In a cap-and-trade system, carbon allowances are allocated or auctioned, and trading begins. Supply and demand determine the market price. Here, Company A emits more CO2 than its allowances cover, and Company B emits less. Company A must buy unused allowances or pay a penalty. Company B can sell its unused allowances to generate revenue.

Source: Carbon Streaming Corp.

What Are Carbon Offsets?

Private entities create carbon offsets that either stop activities that would generate emissions, such as paying landowners not to cut down trees or pay for projects that remove CO2 from the atmosphere, such as planting new trees. Carbon-emitting companies purchase offsets to help them achieve their emission-reduction goals. This funds the activities that sequester or “soak up” carbon.

The most common form of carbon offset comes from planting trees or preserving forests that would otherwise be cut down. Developing renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, is also a popular way to generate carbon offsets. A number of companies around the world are pursuing technologies to capture methane or CO2, which could potentially generate substantial offsets.

Benefits of Carbon Offsets

Carbon offsets add a market-driven cost to using “less expensive” fossil fuels. Businesses responsible for high levels of CO2 emissions must pay more than those reducing their carbon footprints. Companies that reduce emissions below what their allowances permit (in countries with cap-and-trade systems) can benefit financially by selling their unused allowances. These offsets:

Require companies to recognize a financial cost associated with emitting CO2 but do not force them to abandon or radically change current operations.

Help transfer funds from developed to emerging market countries. In buying carbon offsets, companies in countries that are big CO2 emitters provide funding to emerging market countries that suffer disproportionately from the effects of climate change. Emerging markets are home to a large share of the earth’s way of reducing carbon in the atmosphere (think “big forests”).

Ensure a market of potential buyers for technologies that seek to capture emissions from the air. If financially feasible on a large scale, one or more of these technologies could be true game changers. In this sense, the carbon offsets market extends a well-known function of financial intermediation by helping capital to flow to productive uses.

Downsides of Carbon Offsets

Despite the benefits of carbon offsets, there are potential negatives to these costs, including:

Not all carbon offset projects are “legit.” For example, trees naturally capture and store carbon, so carbon offset projects that direct money to protect trees are common, i.e., prevent a forest from being cut down. However, some of these projects “save” trees that were not in danger of being cut down. Money paid for those emission credits could be put to much better use.

Carbon offsets do not necessarily reduce actual carbon levels. In theory, if emission-reduction projects actually removed the emissions generated by, say, burning coal, we should be indifferent between the following choices: a) funding wind, solar, green hydrogen and other non-polluting energy sources to replace coal-fired plants; and b) continuing to burn coal while buying emission credits from projects that capture CO2 and either sequester it or turn it into something harmless. In reality, this is not always the case.

Money companies spend to buy offsets is a real cash outlay, not just a bookkeeping entry. This additional expense could be reduced if customers rewarded companies for making good on promises to cut their carbon footprints.

There is a long lead time between the start of a carbon-reducing project and when it delivers. Trees take a long time to grow; wind and solar farms take years to build from scratch.

Trees burn. Therefore, companies that buy carbon offsets from projects which plant or preserve trees run the risk of their offsets literally going up in flames. Catastrophic fires are occurring with greater frequency in drought-prone areas, destroying the carbon offsets and releasing carbon into the atmosphere, a costly environmental tragedy.

What Investors Should Know About Carbon Credit Markets

The amount spent on carbon credits is projected to grow quickly. Estimates show that in 2020, buyers purchased twice the carbon credits than were bought in 2017. Demand for carbon credits could increase by a factor of 15 or more by 2030 and by a factor of up to 100 by 2050.2

The market for carbon credits could be worth upward of $50 billion in 2030. Does this represent an opportunity for investors? How does it inform an analysis of the cost of achieving emissions-reduction targets for companies in high-polluting industries? Here are some things to consider:

Reducing Emissions Directly Is Better Than Buying Offsets

Reducing emissions directly is a “sure thing” and ultimately lowers costs rather than requiring cash outlays. It’s like choosing between paying a specialty service to clean stains out of your car’s upholstery versus not allowing people to eat or drink in your car in the first place. The cleaning might work but it requires a cash outlay. The second approach requires a small sacrifice but is guaranteed to work. Reducing CO2 emissions directly incentivizes a company to lower its energy use and related expenses based on its specific situation (its factory, vehicle fleet, machinery, etc.).

Is the direct approach feasible? Consider that the people of Finland reduced their electricity use by a whopping 10% in December 2022, the fifth straight month of reductions compared to the same month in 2021.3 This strongly suggests companies could find ways to reduce their power use, thus cutting their CO2. Not only would that help fight climate change, but lower utility bills could also boost profit margins for many companies.

Industries Vary Considerably in CO2 Emissions

There’s a wide difference across industries in terms of their carbon footprints and the ways companies could directly reduce their CO2 emissions instead of buying carbon offsets. Globally, the sectors responsible for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions are electricity and heat generation (utilities), transportation, industrial use, agriculture, and commercial and residential buildings.4

Some industries, such as airlines and trucking, have large carbon footprints because they burn a lot of fuel, not because they use a lot of power from “dirty” power plants. Buying offsets on carbon credit markets may be the only way for them to meaningfully reduce their CO2 emissions until alternative fuels are available and electric vehicles (EVs) are in use on a large scale. Although airlines are seeking to reduce emissions in their ground operations, they are also offsetting emissions from burning jet fuel through the carbon market.

Buying offsets may become quite costly and companies may seek to recoup some of the cost from their customers. Airlines may charge higher fares, as passengers are ultimately the reason an airline flies its planes from A to B. For the trucking industry, converting to EVs will require countries to install fast charging stations across highway systems. Taxpayers may have to cover the cost upfront, although private entities may pool investors’ money to build charging stations, recouping the cost plus a profit over time as more trucks and other drivers use them.

Renewable Energy Credits Are More Reliable

Renewable energy credits (RECs), which are issued when 1 megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity is generated and delivered to the electrical grid from a renewable energy source, are a more reliable type of carbon credit than most others.

Calculating RECs is more accurate than calculating how much CO2 was prevented from entering the atmosphere by planting trees because generating 1 MWh of electricity produced from solar or wind is equivalent to 1 MWh produced from burning oil or coal. RECs can be tracked using a unique identification number to prevent the same REC from being sold to more than one party.

Companies Can Use Both Direct Action and Credits or Offsets

It’s not “one or the other.” It is possible to reduce some emissions by making operational changes — that should be the priority as it is likely more cost-effective and reliable. However, the reality is that the global economy needs energy, and, in some industries, there are currently no green alternatives. (Sustainable aviation fuel is not yet at scale, and battery-powered airplanes are not feasible, so we must depend on jet fuel until new technologies develop.)

It will not be possible to eliminate all carbon emissions; even reducing CO2 by enough to limit the increase in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as per the Paris Agreement, will be extremely challenging. Carbon offsets can help to reduce net emissions now, as we develop new greener technologies, effectively buying time.

Some Entities May Be Dishonest

Let’s face it — when money is involved, some entities will try to game the system, such as by selling carbon offsets from projects that really shouldn’t qualify for them. Independent entities do certify carbon offset projects, but no globally recognized standards dictate how they operate, and no regulatory body oversees them. They have been criticized for a lack of transparency with respect to their methodologies and for overstating effectiveness.

Carbon Credits Could Generate New Sources of Revenue

No-till farming is a sustainable agriculture technique in which stalks, leaves, etc., are buried in a field after a harvest, and the soil is not tilled. Those plant “scraps” hold carbon indefinitely, as long as they are not disturbed. To make this approach financially viable, farmers need to be paid; money from companies that need carbon offsets could generate new revenue for agricultural businesses. Along these lines, producing renewable energy, preserving forests, and carbon capture technologies could use carbon credits they generate to produce new revenue.

Regulations May Support Demand for Carbon Credits

A handful of countries have set legally binding net-zero emission targets, and more are considering doing so. Sweden pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2045, and Denmark, France, Hungary, New Zealand and the UK have made similar pledges for 2050.5 While it is possible that we will see some dramatic breakthroughs in carbon-capture technologies and other green energy solutions over the next 20+ years, meeting these obligations will almost certainly increase demand for carbon credits.

Forestry and Carbon Offsets

Forests contain about a quarter of the world’s carbon, and the loss of forests accounts for about 20% of carbon emissions, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

Timber and agricultural landowners generate most carbon offsets (about 36% per Bloomberg) by deferring or modifying tree harvesting or preventing soil disturbance.

Bloomberg expects forestry to hold the largest carbon credit market increase during the forecast period.

Forestry projects also help prevent significant losses of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

However, forestry shows some of the downsides of the carbon offset market. Carbon emissions calculations from forests are often inaccurate or inconsistent, and carbon credits are often issued for forests or trees that were not going to be harvested at all.

The Role of Emerging Markets in Carbon Offsets

Emerging market (EM) countries play a critical role in the carbon offsets market and are likely to be strongly affected by developments in the supply of and demand for these credits. We also note that several EM countries are both significant emitters and carbon credit issuers.

Carbon offset projects are often located in developing countries. The costs of projects that generate those offsets, such as planting trees, or paying people to stop cutting them down, are significantly cheaper in developing nations than in industrialized countries.

In theory, carbon offset markets benefit EM countries by providing direct financing for projects that might lack capital. There is also potential for benefits beyond carbon as some of these projects, such as building wind farms, can improve livelihoods, create jobs and reduce pollution.

Some view investing in carbon credits in EM countries as exploitative. These are often countries that emit the least but are most likely to feel the effects of climate change. Carbon credits generated by natural assets (such as forests) in EM countries allow big polluters in developed countries to buy the rights to these natural carbon sinks to offset their emissions and continue their environmentally harmful practices.

Case Study: Fighting Deforestation in Brazil

In November 2022, several companies — Itaú (banking), Rabobank (banking), Vale (mining) and Marfrig (meatpacking) — announced a partnership with Suzano (pulp and paper production) and Santader (banking) to form BioMas, a new company focused on combatting deforestation in Brazil. Each partner will invest Real 20 million ($3.8 million).

BioMas expects to finance its projects by selling carbon credits and is looking to earn a profit on the projects. According to a WRI Brasil and New Climate Economy study, it would cost at least Real 19 billion ($3.5 billion) to restore 12 million hectares of forest in the most deteriorated areas of Brazil.

The first project covers a total of 4 million hectares (15,000 square miles) of trees in deforested parts of Brazil, to be financed by selling carbon offset credits on the voluntary market. Initially, BioMas will leverage Suzano’s operational expertise.

The goal is to plant more than 2 billion native trees across 2 million hectares while investing in the conservation of another 2 million hectares of native forests. The work is expected to take 20 years.

Suzano maintains 900,000 hectares of native forest alongside its commercial plantations and has set sustainability targets, including emissions reduction and improved water use in line with the Brazilian Forest Code.

As part of its biodiversity targets, Suzano has pledged to develop and produce 10 million tons of renewable-origin products derived from biomass to replace plastics and other petroleum products and remove the equivalent of 40 million tons of carbon equivalent from the atmosphere.

Sources: Banco Santander, Notice to the Market, November 14, 2022; Dayanne Martins Sousa, “2 Billion New Trees: Suzano, Santander Launch Massive Planting Push in Brazil,” Bloomberg, November 12, 2022; Suzano, “Suzano sets out a new, ambitious long-term biodiversity conservation target,” News Release, June 28, 2021.

Our Perspective

We see the carbon credit market as part of the path to a sustainable economy. Companies should search for operational changes that directly reduce their greenhouse gas emissions because doing so usually saves money in the long run and helps to fight climate change, which is already having devastating and costly effects on communities and businesses everywhere. It also reduces the risk of being exposed to rising prices for carbon offsets, which could become very expensive.

We also believe it is essential that companies purchase verified carbon credits with real transparency into the projects that generate those credits. Otherwise, the risk of greenwashing by paying money for “credits” that in reality do nothing to reduce CO2, is considerable.

Even as the world pushes toward net zero, we know that some emissions will be unavoidable. Therefore, we view carbon offsets as a way to help finance much-needed emission reductions, where the funding cost is borne by entities that do not reduce their emissions directly.

Emerging markets will lead in generating carbon credits, both through their emission-trading schemes and by issuing carbon credits. There is a risk of exploitation that investors should consider when evaluating a company’s use of offsets. More transparency is essential to making carbon credits reliable.

Case Study: ExxonMobil’s Path to Net Zero in the Permian Basin

ExxonMobil recently published a plan to achieve net zero for its Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions from its operations in the Permian Basin by 2030.6 (Scope 1 emissions come directly from sources an entity owns or controls. Scope 2 emissions are indirectly produced when a power plant generates the energy that an entity purchases). The Permian Basin spans southeast New Mexico and West Texas and currently represents over 40% of the company’s net oil and gas production in the U.S.

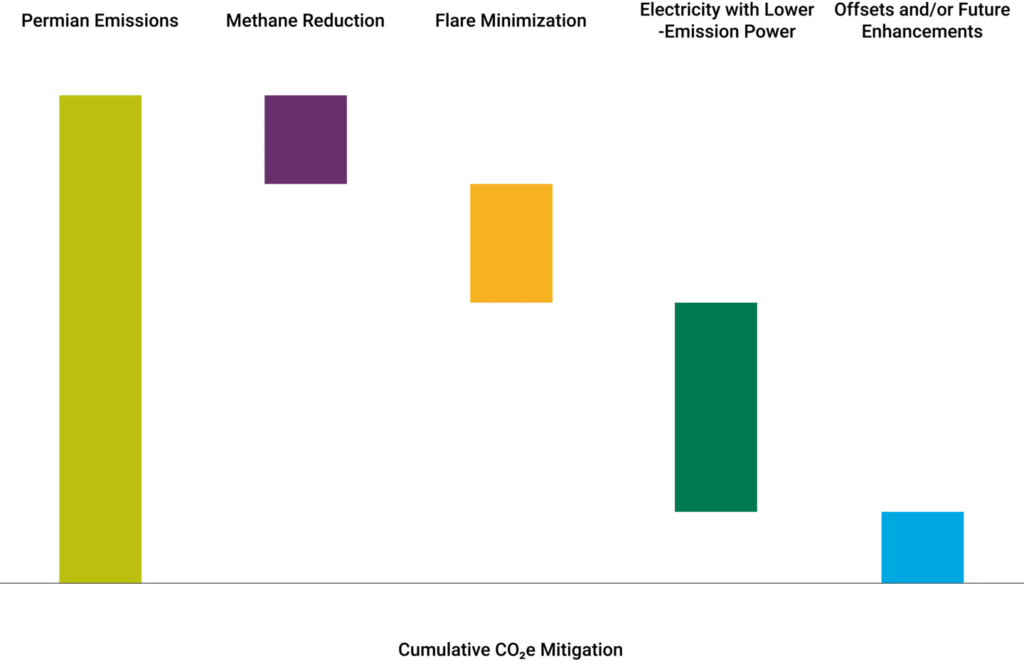

As shown in Figure 2, while carbon credits are a part of this plan, they are not the entire plan or even a major part of it. The company is also making operational changes to reduce emissions, including using low-carbon power, monitoring and fixing methane leaks with aerial imaging technology, optical gas imaging cameras and proprietary acoustic sensors, minimizing flaring and upgrading equipment.

ExxonMobil’s approach to reaching net zero in the Permian Basin shows how a company can use carbon credits as one component of a comprehensive plan. We will continue to monitor the company’s progress toward its stated goal.

Figure 2 ExxonMobil’s Net-Zero Pathway

1World Bank, “Countries on the Cusp of Carbon Markets,” May 24, 2022.

2Christopher Blaufelder, Cindy Levy, Peter Mannion, and Dickon Pinner, “A blueprint for scaling voluntary carbon markets to meet the carbon challenge,” McKinsey Sustainability, January 29, 2021.

3YLE News, “Finland saves even more electricity in December,” January 2, 2023.

4CO2nsensus, “Top 5 Sectors Contributing to Global Warming,” June 29, 2021.

5James Murray, “Which countries have legally-binding net-zero emissions targets?” NS Energy, November 5, 2020.

6ExxonMobil, “ExxonMobil’s Net-Zero Ambition,” Advancing Climate Solutions, 2022 Progress Report Update, July 2022.

References to specific securities are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended as recommendations to purchase or sell securities. Opinions and estimates offered constitute our judgment and, along with other portfolio data, are subject to change without notice.

The opinions expressed are those of American Century Investments (or the portfolio manager) and are no guarantee of the future performance of any American Century Investments’ portfolio. This material has been prepared for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and should not be relied upon for, investment, accounting, legal or tax advice.