There is a widespread view that the world is deglobalising. Asia’s increasing interdependence and its economic strength gives lie to that myth. Global trade will continue to drive emerging Asia’s rapid growth.

Engine of growth

Globalisation has been a powerful engine of growth for Asia, particularly its emerging economies. And it will continue to be – despite widespread fears of deglobalisation. For one thing, global trade isn’t contracting overall, though its nature and composition is changing. Much of that change is rooted in Asia, a by-product of the region’s rapid development, which, in turn, is a function of globalisation.

Indeed, emerging Asia has reached a point where it has everything it needs for sustained growth. It is a collection of diverse and complementary economies – and as such is ever less reliant on the rest of the world. It has an abundance of all the main sources of growth distributed among its interlocked economies: trade; capital; knowledge; and labour.

The deglobalisation myth

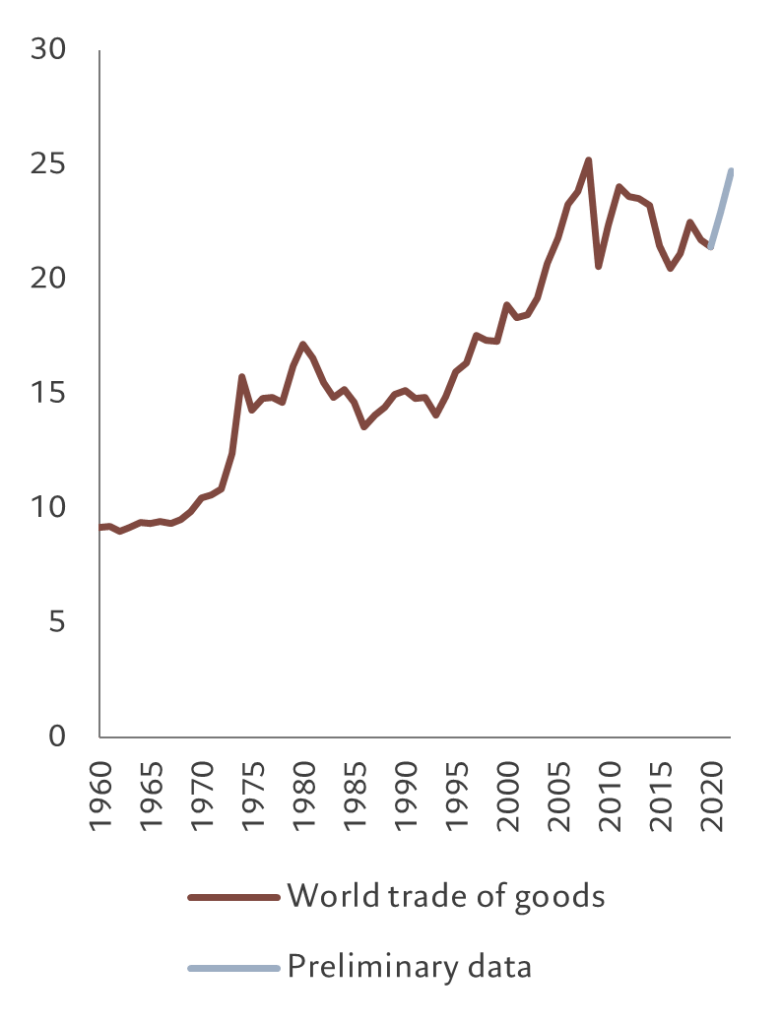

Bearish commentators often fix on the fact that world trade in goods peaked in 2008 and has been on a down-trend since. In doing so they ignore two factors.

The first is that a substantial part of the decline is because China has internalised more of its manufacturing processes as it has developed. So while in the past making a consumer electronics good might have involved shuttling it over the border to, say Taiwan, and back, sometimes two or three or more times, now the whole of the manufacturing process is carried out within China.

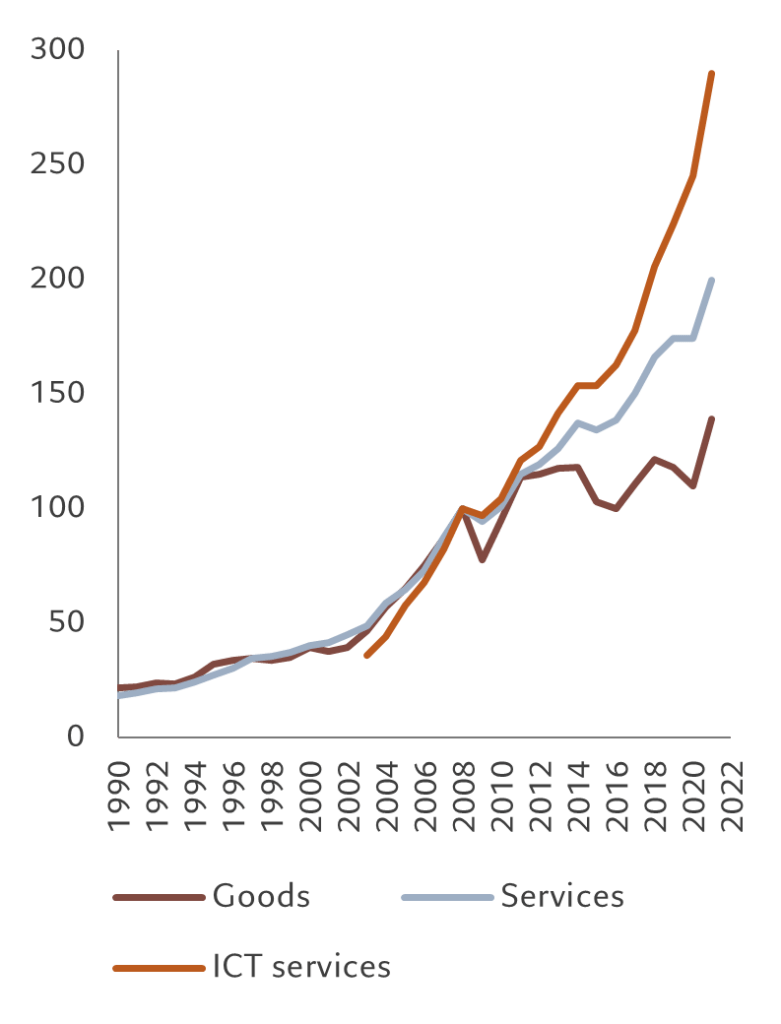

The second oversight is that services exports are growing in importance, but aren’t generally counted in the “globalisation” ledger – global trade in services has nearly doubled since 2008.

Almost certainly, the share of goods trade in world GDP will continue to decline. But that’s largely to do with the rise of services as economies around the world mature. The actual volume of goods trade is likely to grow, in fact preliminary data for 2023 show a sharp upward shift in trade after a decade of broadly sideways movement.

That’s not to say there are no headwinds to trade. For instance, the US re-shored – or brought back to the country from abroad – some 220,000 jobs in 2022.1 Some of this is a post-Covid reaction – firms discovered the fragility of their international supply chains and made efforts to limit future breakdowns. But the trend was already there pre-Covid. Geopolitical tensions have further encouraged reshoring and near-shoring.

But there are limits to reshoring, not least because a country’s competitive advantage in the production of at least some goods and services won’t ever disappear.

At the same time, Covid might have caused disruptions in goods trade, but it opened up new avenues for the expansion of services. It made clear how far communications technology allows services to be internationalised. It’s no longer just a matter of opening call centres in India. Tele-migration has opened up financial, legal, engineering, architectural, consulting, advertising and marketing services – among others – to international competition.

The rise of emerging Asia

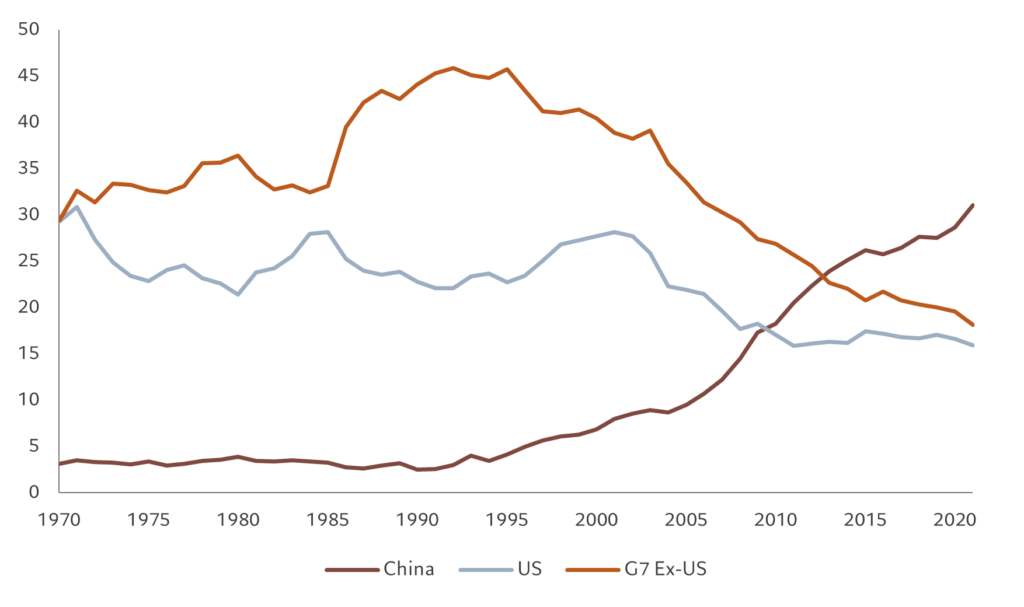

The first wave of globalisation was triggered by steam power. Fast and efficient transportation led to a boom in trade during the 19th century. The gains largely accrued to the most industrialised countries: by 1987, the G7 accounted for nearly 70 per cent of global manufactured goods.2

The latest wave of globalisation has been powered by another innovation – the internet. By driving down the cost of transmitting information, it has accelerated the production and distribution of manufactured goods. This time, Asian producers benefited most. China alone produces 30 per cent of global manufactured goods, with Asia overall accounting for 41 per cent, against 34 per cent for G7 economies (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Chinese powerhouse

% of world manufacturing output

Asia’s dominance in manufactured goods is only likely to strengthen further thanks to the close integration of its economies – not least through trade agreements like ASEAN, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the RCEP – which are both diverse and complementary. Further globalisation could be triggered by yet another innovation – artificial intelligence. It’s worth remembering that China is at the cutting edge of this technology, too.

Four economic blocs

Asia’s economies fit into three emerging blocs and a fourth developed one. Each complements the others in that they all have different strengths in trade, capital, people and information.

China and Hong Kong represent the central bloc – the region’s fulcrum. It dominates regional trade – 25 per cent of developed Asia’s exports go to China, including 40 per cent of Australia’s exports.3 Although it’s the world’s second biggest economy – and heading towards number one spot – China has only a third of the per capita GDP of the region’s most developed countries. It also suffers from poor demographics but is awash with capital, which has allowed it to invest heavily in Asia’s other emerging economies.

The next bloc is made up of less developed countries – largely ASEAN members – on China’s doorstep are sources of cheap and abundant labour, in exchange for which they receive significant capital inflows from richer neighbours. Eighty per cent of their capital inflows comes from China as well as the most developed countries in the region.

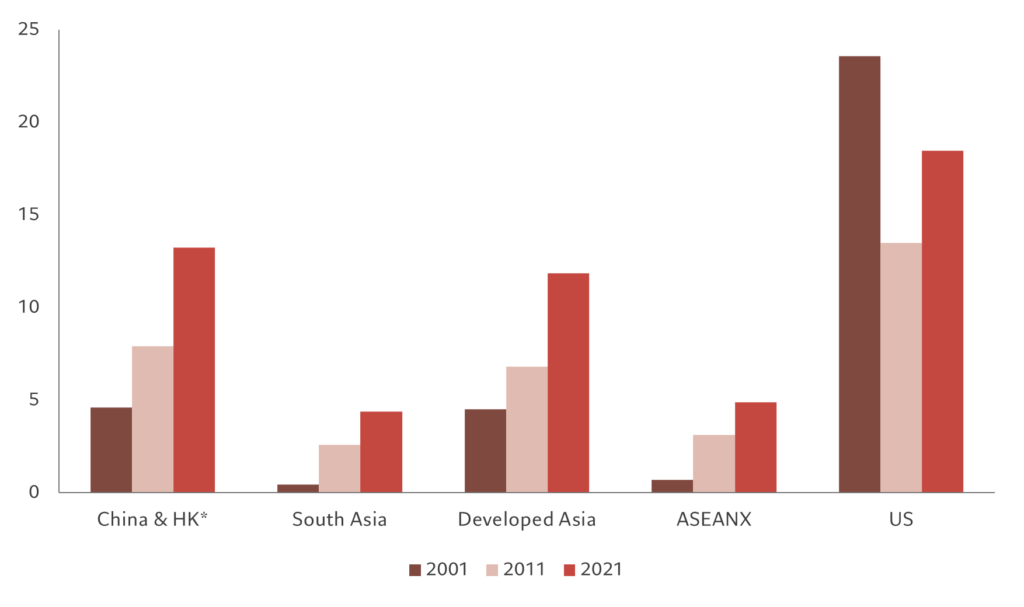

Figure 4 – Where the capital goes

Direct foreign investment into countries and regions, as % of world total, 3-year average

Then there’s the South Asian bloc, which includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. These countries are among the poorest of the region, with only one-twentieth of the GDP per capita of developed Asia. They are also poorly integrated with the rest of the region. But they have the advantages of a very young population and that they have made significant in-roads in business services trade. India alone holds a 13.2 per cent share of world information and communications technology exports, compared to 7.5 per cent for the US. And despite poor trade links with the rest of Asia, the interconnectedness in this sector is growing fast.

Finally, there are the highly developed economies, encompassing Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore. These countries have high levels of GDP per capita, are highly urbanised, are technologically advanced and have surplus capital.

An optimal fit

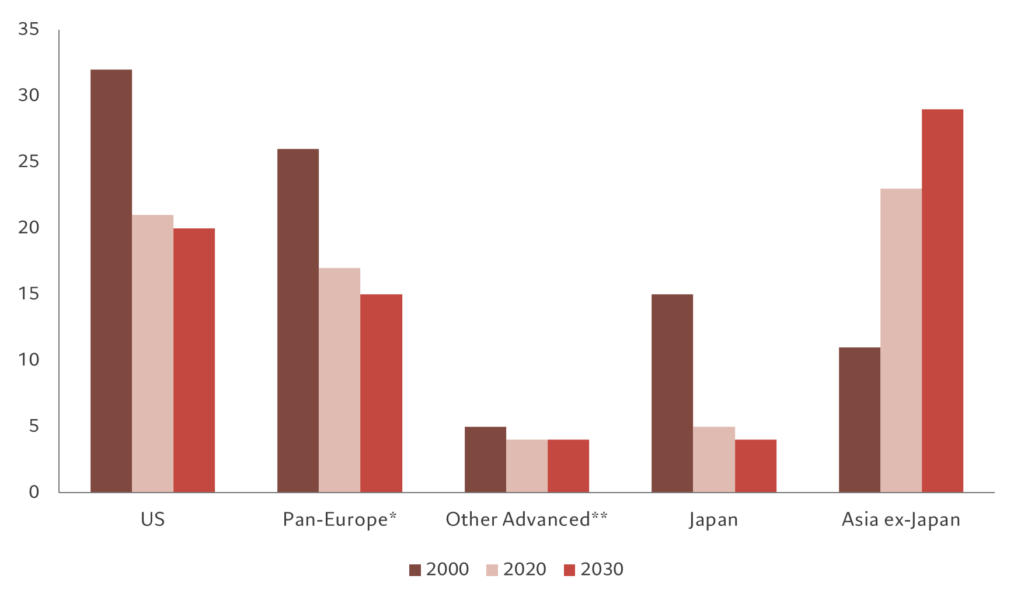

Together, Asian countries can ensure their growth is self-sustaining. Growth potential means that capital will flood in – in 2001, Asia accounted for 10.2 per cent of global capital flows but by 2030 that proportion will grow to 23.64 Over the same period, flows into the US will drop from 23.6 per cent to 18.5 per cent.5 We estimate that by 2030, Asia, including Japan, will account for 33 per cent of global GDP, from 26 per cent in 2000, while the US’s share will drop from 32 per cent to 20 per cent over the same period.6

And as Asia grows in economic importance, it will also take a bigger role in global financial markets. That will mean increasing inclusion in global bond indices. And it is likely to entail the formation of a de facto renminbi bloc. In 2006, there was broadly zero correlation between the Chinese currency and those of other Asian economies. Lately, that’s risen to 20 per cent. In all, the RMB bloc now makes up a quarter of global GDP, equivalent to the euro zone, and as Asian region integration and development progresses, that proportion is only likely to grow.7

Figure 5 – Where the world grows

World share of GDP (in USD), %

Fears about the end of globalisation are generally overdone – but in Asia’s case they are entirely misplaced. The region is becoming increasingly integrated and inter-dependent. Within Asia’s four economic blocs there is enough variation and complementarity that growth can be self-sustaining even where trade in goods might be levelling off in other parts of the world. Covid, rising interest rates and geopolitical tensions have caused Asia’s progress to stutter over recent years, but the region’s upward economic trend has an in-built momentum.

[4] Based on an average over 3 years.

[5] Based on global 3-year average, source Pictet Asset Management and UNCTAD. Data as of February 2023.

[6] Source: Pictet Asset Management, Refinitiv, CEIC. Data as at January 2023.

[7] Monetary zone is estimated as the elasticity-weighted share of 48 economies’ GDP where the elasticity is the reserve currency weight in a given currency using a 2-step Frankel-Wei rolling regression. Source Pictet Asset Management, CEIC, Refinitiv. Data as at Feb 2023.