Yields on government bonds and corporate credits are generous enough to protect investors against considerable market volatility

The investment case for holding bonds and credit is the best it’s been for at least two decades. Yields across the fixed income universe are high enough to protect investors against significant amounts of market volatility and stress in other asset classes while still delivering a positive return.

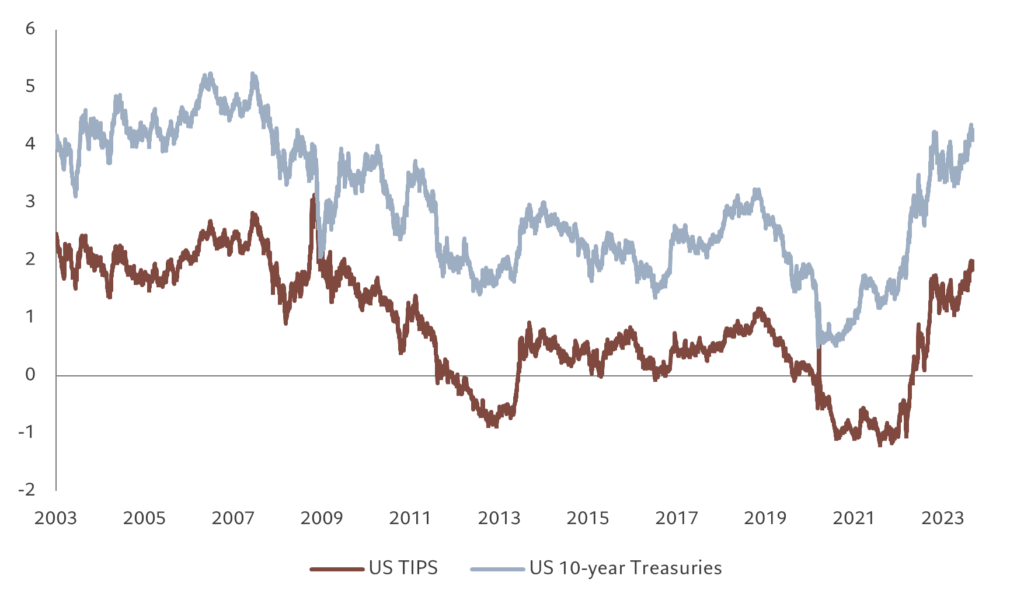

With sovereign bonds and investment grade credit offering nominal yields north of 5 per cent in many cases – in some markets that means real yields of more than 2 per cent – and riskier credits paying in the double digits, the case for bonds is compelling. For example, US 10-year Treasury bonds are yielding around 4.3 per cent against an average of 2.4 per cent for the ten years to 2020 (see Fig. 1). That’s particularly true when comparing bonds with equities, where the equity risk premium has declined sharply over the past year.

The outlook is positive for fixed income under both a hard and soft landing – which I see as the most likely economic scenarios. A hard landing, which is to say a recession caused by central banks seeking to drive inflation back down to their 2 per cent remit at any cost, would push up corporate default rates, but that would broadly be offset by capital appreciation as bonds in general would rally in anticipation of rate cuts to follow, as happened in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008.

Figure 1 – Many happy returns

Yields on US 10-year Treasury bonds and TIPS, %

A soft landing would also generate capital gains as a return to 2 per cent inflation would also mark the beginning of a new monetary easing cycle, but without the negative of a big jump in bond defaults.

The two most worrying scenarios, in our view, sit at the extremes of the range of expectations: the first is that inflation starts to rise again, and central banks are suddenly forced back into a hiking cycle; and the second is the emergence of a deeper economic collapse, in which a hard landing morphs into outright depression. Neither of these is particularly likely, however.

Inflation is unlikely to rebound, not least because the Chinese economy’s weakness is likely to be a deflationary force for the world at large, particularly if China’s policymakers are forced into a significant devaluation of the currency to jump-start exports. At the same time, changes to interest rates act with “long and variable lags” as central bankers put it. Hiking rates from zero to 5 percent or more has been a dramatic shock to the monetary system – albeit more so in some economies than others. Economies where mortgage borrowers are on variable rates or short-dated fixes – such as the UK, Canada and Australia in particular – are most vulnerable to the effects of monetary tightening. By contrast, the US, where households can switch mortgages penalty-free and public spending is flowing – remains relatively insulated though it too will eventually feel the effects of this tightening cycle. Europe is somewhere in-between.

A big buffer

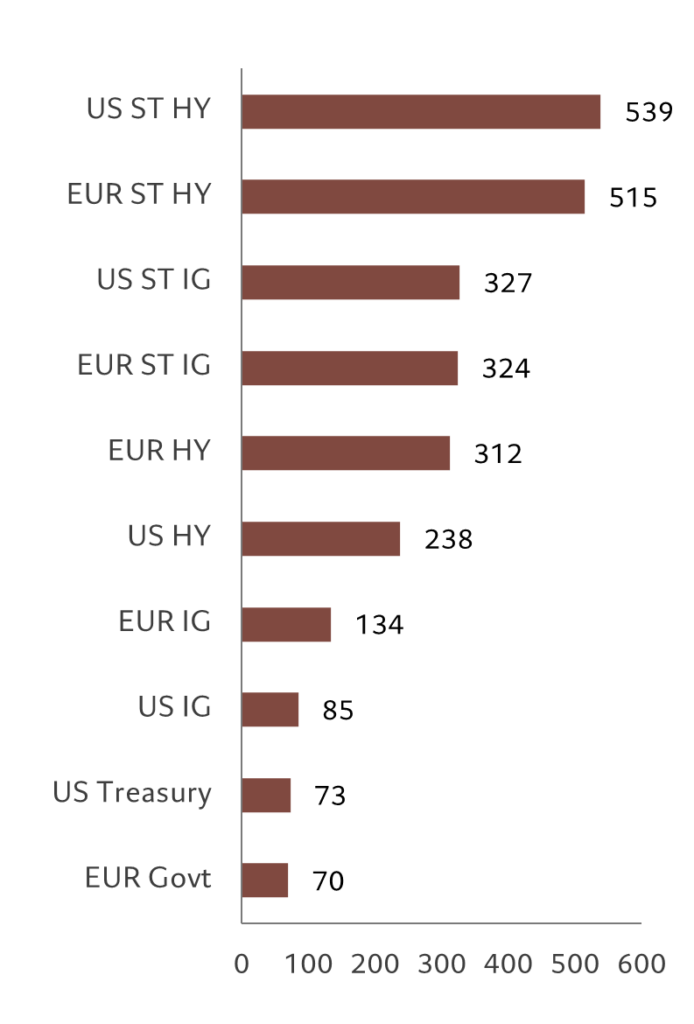

Taking all this into account, we believe interest rates are now very close to their peak and even if they have to go up another 50 or 100 basis points, investors are receiving enough yield to offset any further capital losses. Yields can go up anywhere from 70 basis points in euro zone government bonds to more than 500bps in the case of short-term high yield credit before positive income effects are fully eroded (see Fig. 2).

But even if inflation proves sticky, central bankers will have to weigh the ultimate economic costs of high interest rates in economies so heavily laden with debt, not least government debt. It is likely that they will not only tolerate above-target inflation but even welcome it – as long as it isn’t too far above target – as a means of eroding the value of debt load and therefore reducing the prospect of triggering a catastrophic default crisis later on. So depression is also a less likely prospect, at least in the medium term. Much more likely is that inflation is allowed to run between 3 and 4 per cent for a long period.

That’s not to say parts of the economy won’t struggle. Corporations have already started to feel the strain. Profit margins are coming under pressure from rising wages, while earnings growth is slowing, particularly in segments of the economy where spending is discretionary. Meanwhile, recovery rates on defaulted debt have also started to fall.1

While we think a recession is more likely than not, our expectation is an economic contraction will be met with a quick subsequent mitigation from central banks in the form of rate cuts or fresh quantitative easing, or more targeted liquidity measures, similar to those introduced during the US’s recent banking crisis. Here, keep an eye on developments in the UK economy, which is a canary in the coalmine.

More immediately, we are wary of bonds issued by financial companies. Additional tier-1 (AT1) securities and contingent convertible (CoCos) offer only modest yields, especially when viewed against their volatility in times of stress.2 In other words, we don’t think investors are being paid for the risk they take on in this market. Companies operating in the retail and commodities industries are also heavily leveraged and therefore vulnerable. But there are also plenty of quality investment grade bonds that are trading at steep discounts to par. Some are down to 40 or 50 cents in the dollar, which, if they were to default, have expected recovery rates in the region of 80 cents.

So while we’re bearish on the outlook for the global economy, we are bullish on the asset class. Barring extreme outcomes – a global depression, for instance – sovereign debt and large parts of the credit market offer exceptional value. Indeed, it’s the sort of value last seen in the mid-1980s in some instances.

[1] Recovery rates is the proportion of the total loan that an investor can expect to be repaid in the event of the borrower’s bankruptcy or default.

[2] AT1 and CoCos are types of regulatory capital that a bank is required to hold. They are first in line to take losses in the event that the bank fails and thus higher risk than other types of bonds banks issue.