Key Takeaways

- High-quality companies are less risky than low-quality companies

- The outperformance of high-quality companies over time, as demonstrated by academics, is not the result of hidden risk but is the result of mispricing by investors and analysts

- Those academic findings show that quality, as an investment strategy, can offer sticky, long-term outperformance (because of the result of behavioural causes that are impossible to arbitrage), while offering a defensive behaviour

- Related ProductsWisdomTree Global Quality Dividend Growth UCITS ETF – USD Acc, WisdomTree US Quality Dividend Growth UCITS ETF – USD Acc, WisdomTree Eurozone Quality Dividend Growth UCITS ETF – EUR Acc, WisdomTree UK Quality Dividend Growth UCITS ETF, WisdomTree US Quality Growth UCITS ETF – USD AccFind out more

At WisdomTree, we strongly believe that high-quality companies, defined as high-profitability companies, play a very important role in investors’ portfolios. The success of two of our flagship equity strategies, Quality Dividend Growth, which constructs portfolios around high-quality, dividend-growing companies and Quality Growth, which builds growth portfolios around high-quality companies, is a testament to that belief.

Robert Novy-Marx1 is renowned for describing the high profitability anomaly or quality factor (i.e. the fact that high profitability companies have consistently outperformed the market over time), but he does not stand alone. Practitioners often include quality criteria in their investment process, regardless of their ultimate investment style. Warren Buffett, for example, is famous for focusing on quality, at least as much as value, when he selects companies for investment. There is also a growing body of academic papers documenting that profitability is a predictor of future returns: Fama and French 20062; Ball et al. 2015, 20163.

As well documented as it is, the quality factor remains somewhat mysterious in its root causes. The debate is fierce among academics to decide if hidden risks are the source of the quality premium or if investors’ behaviours and mispricing are the culprits. While academic (pun intended) on the surface, this debate has large repercussions for investors, like WisdomTree, that want to exploit the quality premium:

- A risk-driven factor creates outperformance by taking extra risk, so it tends to be slightly less interesting from a portfolio allocation point of view. It is also technically more capable of being arbitraged and, therefore, more likely to disappear

- A behavioural-driven factor delivers extra return without extra risk, which is, of course, more interesting for investors. It is also more “sticky” as group behaviours are hard to change and hard to arbitrage

More recently, Ahmed, Anwer S. and Neel, Michael and Safdar, Irfan4 proposed a very detailed analysis of the source of this profitability premium, leading to two very important conclusions:

- Firstly, they show that quality behaviour is more consistent with mispricing than with risk

- Secondly, they show that quality is negatively related to the likelihood of large negative future returns but positively related to the likelihood of large positive returns, making quality a unique investment with all-weather qualities

Let’s have a look at those findings in more detail. In their paper, the authors test five important hypotheses leading to the findings above:

Hypothesis one (disproved): Profitability is positively associated with ex-ante downside risk

This first set of analyses shows that more profitable firms are, in fact, less likely to experience future stock crashes. This means that the profitability premium is likely not compensation for investors bearing downside risk when they own high-profit firms. However, it validates WisdomTree’s findings that high-quality companies tend to offer a defensive profile in crisis or high-uncertainty periods.

Hypothesis two (disproved): Profitability is equally and positively associated with price jumps and crashes

The author’s analyses also disprove this hypothesis. They show that profitability is negatively related to the likelihood of large negative future returns but positively related to the likelihood of large positive returns. They demonstrate that high-profitability firms outperform low-profitability firms on days with extremely large negative market returns and days of large positive daily returns. Looking at risk on an ex-post basis, high quality is again shown to be defensive.

Hypothesis three (proven): The abnormal drift in forecast revisions is in the same direction as past profitability and Hypothesis four (proven): The profitability premium is concentrated in (i) high-profit firms with a subsequent upward forecast drift and (ii) low-profit firms with a downward drift

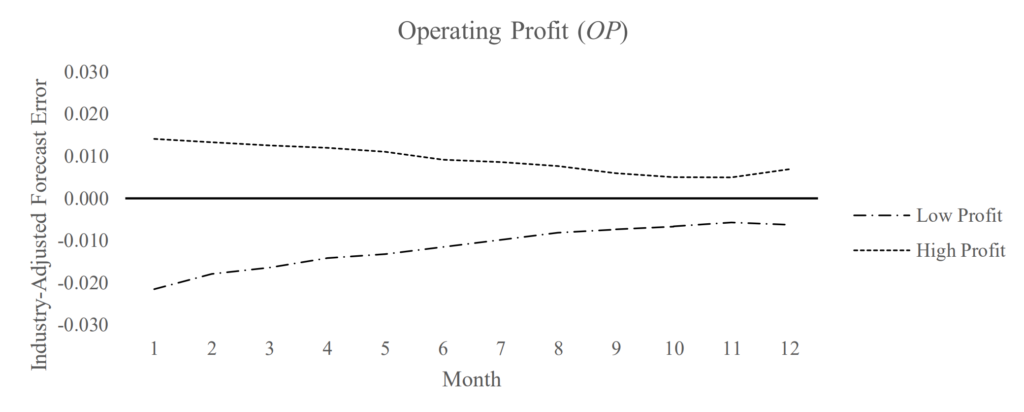

Analyses show that immediately after earning announcements, analysts tend to be pessimistic for high-profit firms and optimistic for low-profit companies. Starting from an amplitude of 1.5% and 1.2% of stock price, this effect tends to attenuate over the following 12 months, leading to the outperformance of high-quality stocks and the underperformance of low-quality stocks

Figure 1: Industry-adjusted forecast errors for low and high operating profitability firms

Hypothesis five (proven): Profitability is positively associated with subsequent institutional demand for shares

In these final analyses, the authors show that institutional investors, like analysts, underreact to good profitability information. They then catch up over the following months, leading to an improvement in the companies’ prices.

Conclusion

In their paper, the authors validated WisdomTree’s firmly held belief about quality investing:

1. Quality companies provide long-term outperformance in a way that is stable over time

2. Quality companies have an all-weather behaviour, being defensive in crisis but also being able to capture returns on the upside

Sources

1 Novy-Marx, R. (2013). The other side of value: The gross operating profitability premium. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(1), 1-28.

2 Fama, E. F., and French, K. R. (2006). Operating profitability, investment, and average returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 491-518.

3 Ball, R., Gerakos, J., Linnainmaa, J. T., and Nikolaev, V. V. (2015). Deflating operating profitability. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(2), 225-248. Ball, R., Gerakos, J., Linnainmaa, J. T., and Nikolaev, V. (2016). Accruals, cash flows, and operating profitability in the cross section of stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 121(1), 28-45

4 Ahmed, Anwer S. and Neel, Michael and Safdar, Irfan, Why Does Operating Profitability Predict Returns? New Evidence on Risk versus Mispricing Explanations (September 9, 2023).