Until recently, the consensus was that China would decouple economically from the developed world. Now we know the separation is not economic but ideological

Decouple – separate, disengage, or dissociate (something) from something else.

“The main element of any United States policy towards the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies” – “X” (George Keenan), Foreign Affairs, July 1, 1947.

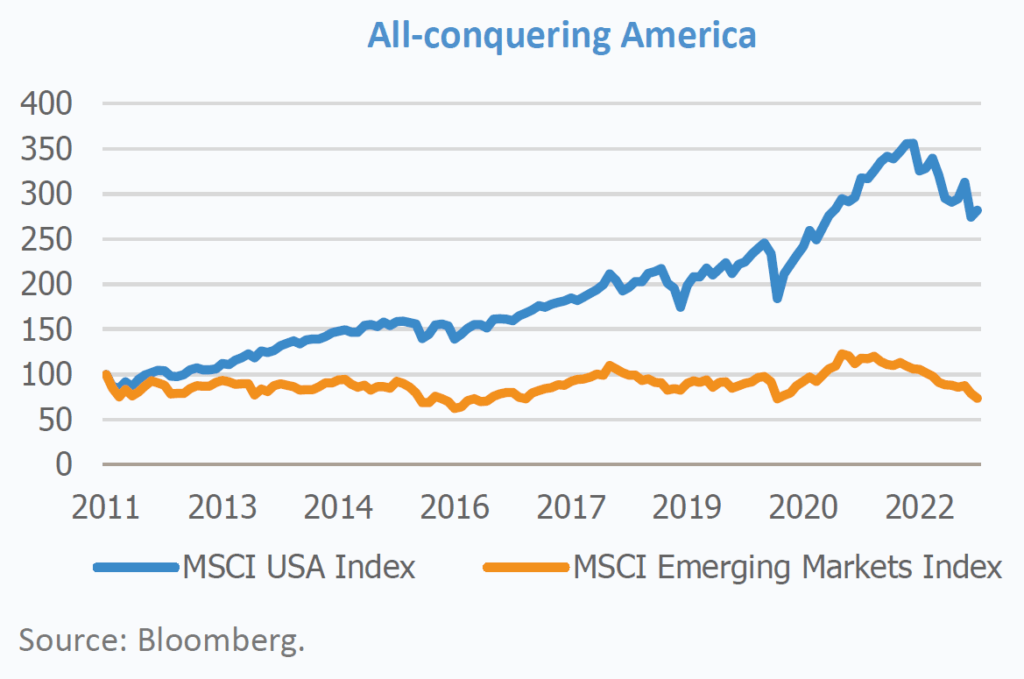

To state the obvious, over the past decade stocks excluding the US have delivered mediocre performance. Since 2009, US stocks have dominated. With a few exceptions, the most successful global businesses across all sectors were US companies. Quite simply, this is a testament to the innovativeness and scalability of US-centric businesses. The success of American companies has lain in their ability to capitalise on network effects, unhindered flows of cheap capital, increased convergence in customer preferences (‘localised globalisation’ thanks to social media) and new, technology-driven business practices, such as moving to the cloud.

As if the underlying cash generating ability of US businesses was not enough, the hegemonic power of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy amplified this dominance by expanding valuation multiples during the long bull market. Yet, when the Fed started to tighten policy, not only did that create severe pressures on non-US businesses (too much debt, liquidity concerns) but it also brutally decimated valuation multiples even lower for the rest of the world.

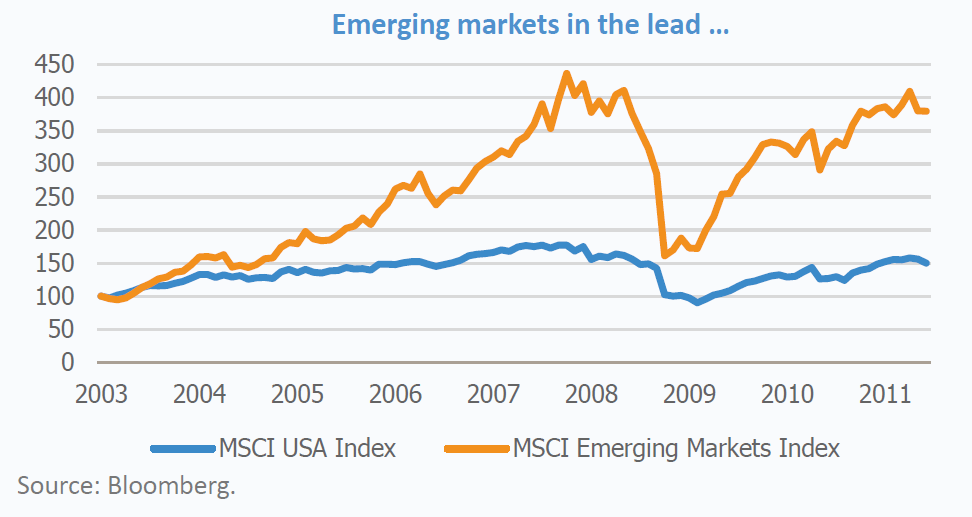

Through the early 2000s, in the wake of the technology bubble collapse of 1999/2000, the US economy reeled from a hangover resulting from an exuberant phase in stock markets, a mood similar to the one we are feeling now. The Federal Reserve had cut rates but the concept of quantitative easing (QE) was not yet in their lexicon. A confluence of events – lower rates, a weaker dollar, easy liquidity, China’s accession to the WTO, long-term underinvestment in commodities, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and low valuations for non-US stocks – led to almost a decade of stellar performance for emerging markets. Despite the housing crisis in the US, looking back at those years, an incipient belief entrenched itself in the minds of politicians, business leaders and fund managers like myself, that we were likely to see a potential decoupling of economic fortunes for Asia from the US That smug feeling of ‘we had arrived’ on the global stage. The US housing and banking crisis in 2008/09 helped cement the notion (misguided as it was) that the US economic and monetary might was on the wane, while its imitators, especially China, were ascendant.

President Xi’s arrival on stage brought a renewed belief in the imminent demise of the ruling hegemonic power, which Xi interpreted as a signal for China to display its strength. Slowly but surely he set the stage to cement his hold on power and purge anyone he considered disloyal or opposed to his ideas. The ‘taking down’ of Jack Ma in 2020 was an early indication that Xi brooked no alternate power structure. In my opinion, he worried that entrepreneurs, using their enormous wealth and social media following, would potentially create conditions to provide a platform for reformists who leaned towards openness in society. That he felt could lead to the gradual demise of the Chinese Communist Party (CPC).

The 20th CPC Congress cemented Xi’s control on power. His choice for key members of the powerful Politburo Standing Committee seems to indicate that what matters most to him is loyalty. In the pre-modern state, particularly in China, Emperors gained control over the State. Yet they rarely exercised complete control over society. President Xi, by contrast, exercises complete control over society in a modern state with technology and surveillance unparalleled in history.

Our long anticipated decoupling is here – only it’s turned out not to be economic, which is what we expected, but to be ideological.

I have no insights nor expertise in reading the tea leaves of Chinese politics. From all that I’ve read (and they are all analysts based outside China – no one in China could say anything that contradicts Xi) the key takeaways for me are:

1. National security is the first order of business for everything. Business, arts, culture, politics, economics, society – everything.

2. The state and only the state can be trusted to direct economic activity towards achieving national security.

3. Political loyalty takes precedence over market credibility and possibly even over technocratic competence (this sounds farfetched but implied in the purge of technocrats from the key levers of power at the top – something we might need to monitor). The echo bubble will likely preclude any negative feedback to Xi personally. He currently has no real counterweight and the norms of institutional behavior, age limits, rule by law (not rule of law) and term limits, are consigned to the dustbins of history.

Markets are hypersensitive to any sign of further politicisation of economic policymaking. The reaction in the stock markets on the day of announcement of the Standing Committee seems to imply that we are in a new era. The old China in which there was a strong consensus on pursuing growth-maximising policies has faded as the independence of technocrats has eroded. Ideology trumps everything.

In late 2020 and early 2021, China’s tilt away from market driven capitalism started to show. The potential risks that could impose on earnings and valuations meant the high valuations and enthusiasm for Chinese stocks could disappoint. Fortunately, we had reduced our China ‘A’ share holdings to almost zero from close to 14% in Q4 2020. I sold off Alibaba the week after Jack Ma was ‘taken down’.

Chinese markets sold off through 2021. By early 2022, risks started shifting to the global economic environment and we reassessed our exposure to China. China’s economy had slowed earlier than the rest of the world. Neither the People’s Bank of China nor the government had engaged in monetary expansion or fiscal transfers anywhere close to central banks and governments in other countries. They had not stimulated the economy as other countries did during Covid. With lower valuations, we perceived this could mean a countercyclical policy initiative from China could be a potential positive for stocks.

What I did not understand was the ideological stubbornness of China’s ‘Zero Covid’ policy. Rationally speaking, the kind of shut downs China imposed meant that the economy and hence job opportunities suffered. Had I used the ideological lens and understood Xi’s authoritarian demands for loyalty and acceptance of his way being the only and correct way, perhaps I would have scaled my exposure to China differently.

As we stand, markets have decisively come to the view that China’s leadership has decoupled from the rest of the world when it comes to economic and ideological philosophies. Innovation, entrepreneurship and wealth accumulation, all attributes of capitalism and free market societies, are under scrutiny in China. I subscribe to that view as we look towards an age of geopolitical rivalry and national security taking center stage. This means, over time our universe of opportunities will likely narrow. Our initial assessment is that few businesses in China will deliver the financial metrics, governance standards and long-term opportunities we look for. In the short term, pessimism towards Chinese stocks is well entrenched for a good reason. In the coming quarters, it is possible that we will get some good news on opening up or a policy-induced cyclical rebound. Yet on a longer-term perspective, the lens through which we assess businesses in China has changed.

Samir Mehta is senior fund manager on the JOHCM Asia ex-Japan Fund. For more information, please click here.

Disclaimer

For professional investors only. This is a marketing communication. Information on the rights of investors can be found here. The registrations of the funds described in this document may be terminated by JOHCM at its discretion from time to time. The investment promoted concerns the acquisition of shares in a fund and not the underlying assets. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency fluctuations and you may not get back the amount originally invested. Emerging Markets may have less stable legal and political systems, which could affect the safe-keeping or value of assets. Investments include shares in small-cap companies and these tend to be traded less frequently and in lower volumes than larger companies making them potentially less liquid and more volatile. Investments include shares in small-cap companies and these tend to be traded less frequently and in lower volumes than larger companies making them potentially less liquid and more volatile. The information contained herein including any expression of opinion is for information purposes only and is given on the understanding that it is not a recommendation.